We are not for sale

If you're waiting for Wikipedia to be bought by your friendly neighborhood Internet giant, don't hold your breath. Wikipedia is a non-commercial website run by the Wikimedia Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization based in San Francisco.

(Fig. 24.35B); they are toxic to grazing animals, particularly to sheep. The highest incidence of livestock losses attributable to lupine alkaloid poisoning occurs in autumn during the seed‐bearing stage of the plant life cycle—the seeds being the plant parts that accumulate the greatest quantities of these alkaloids. Because of their bitter taste, lupine alkaloids can also function as feeding deterrents. Given a mixed population of sweet and bitter lupines, rabbits and hares readily eat the alkaloid‐free sweet variety and avoid the lupine alkaloid‐accumulating bitter variety, indicating that lupine alkaloids can reduce herbivory by functioning both as bitter‐tasting deterrents and toxins. Given this collection of examples, alkaloids can be viewed as a part of the chemical defense system of the plant that evolved under the selection pressure of predation.

FIGURE 24.28 Structure of the anticholinergic tropane alkaloid

atropine from Hyoscyamus niger.

Hyoscyamus Niger

https://www.pinkyparadise.com/.../hunter-eyes-vs-prey-eyes

What are hunter eyes?

Hunter eyes are characterized by a deep-set, intense look, a more prominent brow ridge, and a horizontally narrow appearance.

Evolutionarily, these eyes are believed to be adapted for focused vision, aiding in hunting and tracking. Aesthetically, hunter eyes are often associated with strength and determination, contributing to a more masculine or assertive appearance.

FIGURE 24.27 (A) The piperidine alkaloid coniine, the first alkaloid to be synthesized, is extremely toxic, causing paralysis of motor nerve endings. (B) In 399 bc, the philosopher Socrates was executed by consuming an extract of coniine‐containing poisonous hemlock. This depiction of the event, “The Death of Socrates,” was painted by Jacques‐Louis David in 1787.

Source: (B) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

Papaver somniferum

FIGURE 24.29 (A) Structures of the alkaloids codeine and morphine from the opium poppy Papaver somniferum. Asymmetric (chiral) carbons are highlighted with red dots. (B) The frog Bufo marinus accumulates a considerable amount of morphine in its skin. (C) Structure of diacetyl morphine, commonly known as heroin.

Source: (B) Rickl, Universität München, Germany; previously unpublished.

AI Overview

Learn more…Opens in new tab

The shape of an animal's eyes can indicate whether it is an ambush predator or a hunter, and can reveal other information about its ecological niche:

-

Ambush predatorsThese animals have vertical slit pupils and are active day and night. They use stealth to overcome their prey. For example, domestic cats and geckos have vertical slit pupils.

-

HuntersThese animals have circular pupils and chase down their prey. For example, humans and birds have circular pupils.

-

Prey animalsThese animals have horizontally elongated pupils and are plant-eaters. For example, goats and sheep have horizontally elongated pupils.

Here are some other things to know about the eyes of predators and prey:

-

Binocular visionVertical slit pupils and binocular vision help ambush predators judge distance precisely.

-

Depth perceptionVertical slit pupils help ambush predators optimize their depth perception.

-

Field of viewHorizontal slit pupils help prey animals optimize their field of view.

-

LightHorizontal slit pupils help prey animals get more light from the sides and less from above.

-

Eye positionPredators often have eyes located in the front of their skull to focus on and target their prey.

Alkaloids are thought to be part of the direct chemical defense

system of many plants, and in some cases, such as that of nicotine in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), convincing evidence

has been presented that an alkaloid is involved in induced

chemical defense. Wild species of tobacco are highly toxic to the hornworm Manduca sexta, a tobacco‐adapted species. Feeding by larvae of M. sexta on its host plant Nicotiana attenuata elicits responses from the plant that are distinguishable from mechanical simulation of the damage that results from feeding. Mechanical damage induces accumulation of the plant hormone jasmonic acid (see Chapter 17) in the wounded leaf, and that systemically results in an accumulation of nicotine in the whole plant. Feeding by the tobacco hornworm results in higher leaf jasmonic acid levels than mechanical wounding, but whole plant nicotine levels do not surpass those achieved with mechanical damage. Hornworm feeding, in particular chemicals present in hornworm regurgitant, interferes with whole plant accumulation of nicotine, and it appears that the plant hormone ethylene (see Chapter 17) is specifically elicited by hornworm herbivory. The interplay between jasmonic acid and ethylene regulates nicotine biosynthesis and accumulation that results from insect attack of the tobacco plant. To determine whether nicotine actually functions in defense required down regulating the nicotine biosynthesis gene that encodes putrescine N‐methyl transferase in N. attenuata using RNA interference (RNAi) technology. This reduced constitutive and inducible nicotine levels by greater than 95% in the transgenic plants. Larvae of the tobacco hornworm (Fig. 24.36) grew faster and preferred transgenic plants with reduced nicotine in choice tests. When planted in their native habitat, the low nicotine, transgenic plants were attacked more frequently and lost more leaf area to a variety of native herbivores compared to wild‐type plants that contained normal levels of nicotine. Nicotine down-regulated plants were also used to demonstrate a role for this alkaloid in reproductive fitness of Nicotiana flowers (Box 24.10). Nicotine has a role in reproductive fitness of Nicotiana attenuata flowers Flowers produce distinctive combinations (bouquets) of volatile secondary metabolites that aid reproduction by attracting pollinators. Another familiar example of a floral reproductive aid is flower color, which can attract specific pollinators, such as hummingbirds or bees. Flowers face a diverse challenge in that they must attract a pollinator, but must also repel florivores and nectar

thieves, which do not contribute to pollen transfer.

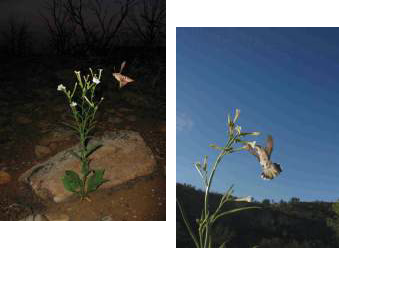

The combination of the secondary metabolites

nicotine and benzylacetone in flowers of Nicotiana

attenuata, a tobacco species native to western North

America, optimizes reproductive fitness. N. attenuata

flowers attract the moth Hyles lineata (A) and the

hummingbird Archilochus alexandri (B) as pollinators.

Using genetic engineering, N. attenuata plants have been

designed to lack nicotine, benzylacetone, or both nicotine

and benzylacetine. When these metabolically tailored

plants were tested in the wild for fitness, the plants that

contained both nicotine and benzylacetone in their floral

blend sired more seeds on other plants and produced

larger seed capsules themselves. Benzylacetone attracts

visitors to a flower, while nicotine prevents visitors from

loitering while also deterring florivory by caterpillars and

nectar robbing by carpenter bees. Combinations of

attractants and repellents can help flowers to attract

mates while avoiding predators, a pull and push strategy

that optimizes a visitor’s behavior. Source: Kessler, Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Jena, Germany.

Conium Maculatum

Flowering plants (angiosperms) comprise ∼90% of the plant kingdom. The total number of described species exceeds 230,000, and many tropical species are as yet unnamed. During the past 130 million years, flowering plants have colonized practically every conceivable habitat on earth, from deserts and alpine summits, to fertile grasslands, freshwater marshes, dense forests, and lush mountain meadows. The total number of plant species, which are cultivated as agricultural, forest, or horticultural crops, can be estimated to be close to 7,000 botanical species. Nevertheless, it is often stated that only 30 species “feed the world”, because the major crops are made up by a very limited number of species. Distinguished by FAO, tropical and subtropical fruit and nut crop species represent 30% of the 150 primary food crops, and together provide more than 15% of the world's human food supply. The major commodity crops, wheat, rice and maize, are critical to providing energy in diets. Their evolution dates back more than 9,000 years (cf. Tab. 56). The three largest flowering plant families containing the greatest number of species are the sunflower family (Asteraceae) with ∼24,000 species, the orchid family (Orchidaceae; Ophioglossum reticulatum has the highest known diploid chromosome number 2n = 1,260) with ∼20,000 species, and the legume or pea family (Fabaceae) with 18,000 species. The total number of species for these three enormous families alone is approximately 62,000, roughly 25% of all the flowering plant species on earth.

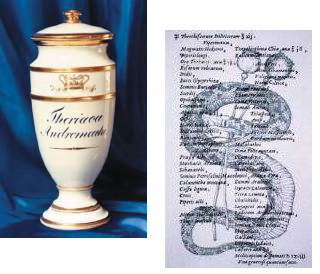

One of the oldest and most long‐lived medications in

the history of mankind is Theriak. Originating in

Greco‐Roman culture, Theriak consists of mainly opium

and wine with a variety of plant, animal, and mineral constituents.

Panel A of the figure shows a recipe for Theriak

from the French Pharmacopée Royale in 1676.

Theriak was developed as an antidote against poisoning,

snake and spider bites, and scorpion stings. History has it

that the Roman Emperor Nero contracted the Greek

physician Andromachus to discover a medicine that was

effective against all diseases and poisons. Andromachus

improved the then‐existing recipe to include, in addition to

opium, five other plant poisons and 64 plant drugs. Another

crucial component was dried snake meat, believed to act

against snakebite by neutralizing the venom.

Today, Theriak is still prescribed in rare cases in Europe

for pain and other ailments. Panel B shows a valuable

Theriak‐holding vessel made of Nymphenburg porcelain

(in about 1820), which is on display in the Residenz

Pharmacy in Munich, Germany.

Source: (A) French Pharmacopée Royale; photograph:

Kutchan, Leibnitz Institut für Pflanzenbiochemie, Halle,

Germany; previously unpublished; (B) Residenz Pharmacy,

Munich, Germany; photograph: Kutchan, Leibnitz Institut für

Pflanzenbiochemie, Halle, Germany; previously unpublished.

This is a book about cancer: its ancient origins, its modern manifestations, and its future fate. It is a book about where cancer came from, why it exists, and why it is so hard to cure. This is also a book about a new way of looking at cancer—not as something that must be eliminated at all costs, but rather as something that must be controlled and shaped into a companion that we can live with. Life has struggled with cancer since the dawn of multicellularity about two billion years ago. When we think of life on Earth, we typically think of multicellular organisms like animals and plants that are made up of more than one cell. The cells in a multicellular organism essentially divide the labor of making a living, cooperating, and coordinating to do all the functions that are needed in the body. On the other hand, unicellular life forms—like bacteria, yeasts, and protists—are made of a single cell that does all of the jobs of keeping that cell alive. Unicellular life dominated our planet for billions of years before multicellular life gained an evolutionary foothold. The world was cancer-free during these two billion years 2 Cha pter 1 when unicellular life reigned. But when multicellular life entered the scene, it ushered in a new player: cancer. Cancer is a part of us, and it has been since our very beginnings as multicellular organisms. Remnants of cancers have been found in the skeletons of ancient humans, from Egyptian mummies to Central and South American hunter-gatherers. Cancer has been found in 1.7-million-year-old bones of our early human ancestors in “the cradle of humankind” in South Africa. Fossil evidence of cancer goes back further still; it is found in bones tens and even hundreds of millions of years old, from mammals, fish, and birds. Cancer goes back as far as the days when dinosaurs dominated life on our planet, and back even further than that, to a time when life was microscopically small. Cancer began before most of life as we know it even existed. In order to manage cancer effectively, we must understand the evolutionary and ecological dynamics that underlie it. But we must also change our way of thinking about cancer, from viewing it as a temporary and tractable challenge to seeing it as a part of who we are as multicellular beings. Before multicellular life evolved, cancer did not exist because there were no bodies for cancer cells to proliferate inside of and ultimately invade. But once multicellular life emerged, cancer was able to emerge as well. Our very existence as multicellular organisms—as paragons of multicellular cooperation—is inextricably tied to our susceptibility to cancer. In this book we will see how our bodies are made of cells that cooperate in myriad ways to make us functional multicellular organisms—for example, by controlling cell proliferation, distributing resources to cells that need them, and building complex organs and tissues. We will also see how cancer can evolve to exploit the cooperative cellular nature of our bodies: proliferating out of control, exploiting the resources in our bodies, and even turning our tissues into specialized niches for their own survival. In a word, cancer is cheating in the game that forms the most fundamental foundations of multicellular life. A better understanding of the essential nature of cancer can help us to prevent and treat it more effectively, and also help us to see that we are not alone in our struggles with cancer. All forms of multicellular life are affected by cancer. Our evolutionary relationship with cancer has shaped who we are. And if we want to truly understand what cancer is, we must understand how it evolved and how we evolved along with it.

Hundreds of years ago, bankers began to specialize, with the richer and more influential ones associated increasingly with foreign trade and foreign-exchange transactions. Since these were richer and more cosmopolitan and increasingly concerned with questions of political significance, such as stability and debasement of currencies, war and peace, dynastic marriages, and worldwide trading monopolies, they became the financiers and financial advisers of governments. Moreover, since their relationships with governments were always in monetary terms and not real terms, and since they were always obsessed with the stability of monetary exchanges between one country’s money and another, they used their power and influence to do two things: (1) to get all money and debts expressed in terms of a strictly limited commodity—ultimately gold; and (2) to get all monetary matters out of the control of governments and political authority, on the ground that they would be handled better by private banking interests in terms of such a stable value as gold. These efforts failed with the shift of commercial capitalism into mercantilism and the destruction of the whole pattern of social organization based on dynastic monarchy, professional mercenary armies, and mercantilism, in the series of wars which shook Europe from the middle of the seventeenth century to 1815. Commercial capitalism passed through two periods of expansion each of which deteriorated into a later phase of war, class struggles, and retrogression. The first stage, associated with the Mediterranean Sea, was dominated by the North Italians and Catalonians but ended in a phase of crisis after 1300, which was not finally ended until 1558. The second stage of commercial capitalism, which was associated with the Atlantic Ocean, was dominated by the West Iberians, the Netherlanders, and the English. It had begun to expand by 1440, was in full swing by 1600, but by the end of the seventieth century had become entangled in the restrictive struggles of state mercantilism and the series of wars which ravaged Europe from 1667 to 1815. The commercial capitalism of the 1440-1815 period was marked by the supremacy of the Chartered Companies, such as the Hudson’s Bay, the Dutch and British East Indian companies, the Virginia Company, and the Association of Merchant Adventurers (Muscovy Company). England’s greatest rivals in all these activities were defeated by England’s greater power, and, above all, its greater security derived from its insular position.

TRAGEDY AND HOPE A History of THE WORLD in Our Time

Carroll Quigley

Europe’s Shift to the Twentieth Century

While Europe’s traits were diffusing outward to the non-European world, Europe was also undergoing profound changes and facing difficult choices at home. These choices were associated with drastic changes; in some cases we might say reversals, of Europe’s point of view. These changes may be examined under eight headings. The nineteenth century was marked by (i) belief in the innate goodness of man; (2) secularism; (3) belief in progress; (4) liberalism; (5) capitalism; (6) faith in science; (7) democracy; (8) nationalism. In general, these eight factors went along together in the nineteenth century. They were generally regarded as being compatible with one another; the friends of one were generally the friends of the others; and the enemies of one were generally the enemies of the rest. Metternich and De Maistre were generally opposed to all eight; Thomas Jefferson and John Stuart Mill were generally in favor of all eight. The belief in the innate goodness of man had its roots in the eighteenth century when it appeared to many that man was born good and free but was everywhere distorted, corrupted, and enslaved by bad institutions and conventions. As Rousseau said, “Man is born free yet everywhere he is in chains.” Thus arose the belief in the “noble savage,” the romantic nostalgia for nature and for the simple nobility and honesty of the inhabitants of a faraway land. If only man could be freed, they felt, freed from the corruption of society and its artificial conventions, freed from the burden of property, of the state, of the clergy, and of the rules of matrimony, then man, it seemed clear, could rise to heights undreamed of before—could, indeed, become a kind of superman, practically a god. It was this spirit which set loose the French Revolution. It was this spirit which prompted the outburst of self-reliance and optimism so characteristic of the whole period from 1770 to 1914. Obviously, if man is innately good and needs but to be freed from social restrictions, he is capable of tremendous achievements in this world of time, and does not need to postpone his hopes of personal salvation into eternity. Obviously, if man is a godlike creature whose ungodlike actions are due only to the frustrations of social conventions, there is no need to worry about service to God or devotion to any otherworldly end. Alan can accomplish most by service to himself and devotion to the goals of this world. Thus came the triumph of secularism. Closely related to these nineteenth century beliefs that human nature is good, that society is bad, and that optimism and secularism were reasonable attitudes were certain theories about the nature of evil. To the nineteenth century mind evil, or sin, was a negative conception. It merely indicated a lack or, at most, a distortion of good. Any idea of sin or evil as a malignant positive force opposed to good, and capable of existing by its own nature, was completely lacking in the typical nineteenth-century mind. To such a mind the only evil was frustration and the only sin, repression. Just as the negative idea of the nature of evil flowed from the belief that human nature was good, so the idea of liberalism flowed from the belief that society was bad. For, if society was bad, the state, which was the organized coercive power of society, was doubly bad, and if man was good, he should be freed, above all, from the coercive power of the state. Liberalism was the crop which emerged from this soil. In its broadest aspect liberalism believed that men should be freed from coercive power as completely as possible. In its narrowest aspect liberalism believed that the economic activities of man should be freed completely from “state interference.” This latter belief, summed up in the battle-cry “No government in business,” was commonly called “laissez-faire.” Liberalism, which included laissez-faire, was a wider term because it would have freed men from the coercive power of any church, army, or other institution, and would have left to society little power beyond that required to prevent the strong from physically oppressing the weak. From either aspect liberalism was based on an almost universally accepted nineteenth-century superstition known as the “community of interests.” This strange, and unexamined, belief held that there really existed, in the long run, a community of interests between the members of a society. It maintained that, in the long run, what was good for one member of society was good for all and that what was bad for one was bad for all. But it went much further than this. The theory of the “community of interests” believed that there did exist a possible social pattern in which each member of society would be secure, free, and prosperous, and that this pattern could be achieved by a process of adjustment so that each person could fall into that place in the pattern to which his innate abilities entitled him. This implied two corollaries which the nineteenth century was prepared to accept: (1) that human abilities are innate and can only be distorted or suppressed by social discipline and (2) that each individual is the best judge of his own self-interest. All these together form the doctrine of the “community of interests,” a doctrine which maintained that if each individual does what seems best for himself the result, in the long run, will be best for society as a whole. Closely related to the idea of the “community of interests” were two other beliefs of the nineteenth century: the belief in progress and in democracy. The average man of 1880 was convinced that he was the culmination of a long process of inevitable progress which had been going on for untold millennia and which would continue indefinitely into the future. This belief in progress was so fixed that it tended to regard progress as both inevitable and automatic. Out of the struggles and conflicts of the universe better things were constantly emerging, and the wishes or plans of the objects themselves had little to do with the process. The idea of democracy was also accepted as inevitable, although not always as desirable, for the nineteenth century could not completely submerge a lingering feeling that rule by the best or rule by the strong would be better than rule by the majority. But the facts of political development made rule by the majority unavoidable, and it came to be accepted, at least in Western Europe, especially since it was compatible with liberalism and with the community of interests. Liberalism, community of interests, and the belief in progress led almost inevitably to the practice and theory of capitalism. Capitalism was an economic system in which the motivating force was the desire for private profit as determined in a price system. Such a system, it was felt, by seeking the aggrandization of profits for each individual, would give unprecedented economic progress under liberalism and in accord with the community of interests. In the nineteenth century this system, in association with the unprecedented advance of natural science, had given rise to industrialism (that is, power production) and urbanism (that is, city life), both of which were regarded as inevitable concomitants of progress by most people, but with the greatest suspicion by a persistent and vocal minority. The nineteenth century was also an age of science. By this term we mean the belief that the universe obeyed rational laws which could be found by observation and could be used to control it. This belief was closely connected with the optimism of the period, with its belief in inevitable progress, and with secularism. The latter appeared as a tendency toward materialism. This could be defined as the belief that all reality is ultimately explicable in terms of the physical and chemical laws which apply to temporal matter. The last attribute of the nineteenth century is by no means the least: nationalism. It was the great age of nationalism, a movement which has been discussed in many lengthy and inconclusive books but which can be defined for our purposes as “a movement for political unity with those with whom we believe we are akin.” As such, nationalism in the nineteenth century had a dynamic force which worked in two directions. On the one side, it served to bind persons of the same nationality together into a tight, emotionally satisfying, unit. On the other side, it served to divide persons of different nationality into antagonistic groups, often to the injury of their real mutual political, economic, or cultural advantages. Thus, in the period to which we refer, nationalism sometimes acted as a cohesive force, creating a united Germany and a united Italy out of a medley of distinct political units. But sometimes, on the other hand, nationalism acted as a disruptive force within such dynastic states as the Habsburg Empire or the Ottoman Empire, splitting these great states into a number of distinctive political units. These characteristics of the nineteenth century have been so largely modified in the twentieth century that it might appear, at first glance, as if the latter were nothing more than the opposite of the former. This is not completely accurate, but there can be no doubt that most of these characteristics have been drastically modified in the twentieth century. This change has arisen from a series of shattering experiences which have profoundly disturbed patterns of behavior and of belief, of social organizations and human hopes. Of these shattering experiences the chief were the trauma of the First World War, the long-drawn-out agony of the world depression, and the unprecedented violence of destruction of the Second World War. Of these three, the First World War was undoubtedly the most important. To a people who believed in the innate goodness of man, in inevitable progress, in the community of interests, and in evil as merely the absence of good, the First World War, with its millions of persons dead and its billions of dollars wasted, was a blow so terrible as to be beyond human ability to comprehend. As a matter of fact, no real success was achieved in comprehending it. The people of the day regarded it as a temporary and inexplicable aberration to be ended as soon as possible and forgotten as soon as ended. Accordingly, men were almost unanimous, in 1919, in their determination to restore the world of 1913. This effort was a failure. After ten years of effort to conceal the new reality of social life by a facade painted to look like 1913, the facts burst through the pretense, and men were forced, willingly or not, to face the grim reality of the twentieth century. The events which destroyed the pretty dream world of 1919-1929 were the stock-market crash, the world depression, the world financial crisis, and ultimately the martial clamor of rearmament and aggression. Thus depression and war forced men to realize that the old world of the nineteenth century had passed forever, and made them seek to create a new world in accordance with the facts of present-day conditions. This new world, the child of the period of 1914-1945, assumed its recognizable form only as the first half of the century drew to a close. In contrast with the nineteenth-century belief that human nature is innately good and that society is corrupting, the twentieth century came to believe that human nature is, if not innately bad, at least capable of being very evil. Left to himself, it seems today, man falls very easily to the level of the jungle or even lower, and this result can be prevented only by training and the coercive power of society. Thus, man is capable of great evil, but society can prevent this. Along with this change from good men and bad society to bad men and good society has appeared a reaction from optimism to pessimism and from secularism to religion. At the same time the view that evil is merely the absence of good has been replaced with the idea that evil is a very positive force which must be resisted and overcome. The horrors of Hitler’s concentration camps and of Stalin’s slave-labor units are chiefly responsible for this change. Associated with these changes are a number of others. The belief that human abilities are innate and should be left free from social duress in order to display themselves has been replaced by the idea that human abilities are the result of social training and must be directed to socially acceptable ends. Thus liberalism and laissez-faire are to be replaced, apparently, by social discipline and planning. The community of interests which would appear if men were merely left to pursue their own desires has been replaced by the idea of the welfare community, which must be created by conscious organizing action. The belief in progress has been replaced by the fear of social retrogression or even human annihilation. The old march of democracy now yields to the insidious advance of authoritarianism, and the individual capitalism of the profit motive seems about to be replaced by the state capitalism of the welfare economy. Science, on all sides, is challenged by mysticisms, some of which march under the banner of science itself; urbanism has passed its peak and is replaced by suburbanism or even “flight to the country”; and nationalism finds its patriotic appeal challenged by appeals to much wider groups of class, ideological, or continental scope. We have already given some attention to the fashion in which a number of western-European innovations, such as industrialism and the demographic explosion, diffused outward to the peripheral non-European world at such different rates of speed that they arrived in Asia in quite a different order from that in which they had left western Europe. The same phenomenon can be seen within Western Civilization in regard to the nineteenth-century characteristics of Europe which we have enumerated. For example, nationalism was already evident in England at the time of the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588; it raged through France in the period after 1789; it reached Germany and Italy only after 1815, became a potent force in Russia and the Balkans toward the end of the nineteenth century, and was noticeable in China, India, and Indonesia, and even Negro Africa, only in the twentieth century. Somewhat similar patterns of diffusion can be found in regard to the spread of democracy, of parliamentary government, of liberalism, and of secularism. The rule, however, is not so general or so simple as it appears at first glance. The exceptions and the complications appear more numerous as we approach the twentieth century. Even earlier it was evident that the arrival of the sovereign state did not follow this pattern, enlightened despotism and the growth of supreme public authority appearing in Germany, and even in Italy, before it appeared in France. Universal free education also appeared in central Europe before it appeared in a western country like England. Socialism also is a product of central Europe rather than of Western Europe, and moved from the former to the latter only in the fifth decade of the twentieth century. These exceptions to the general rule about the eastward movement of modern historical developments have various explanations. Some of these are obvious, but others are very complicated. As an example of such a complication we might mention that in Western Europe nationalism, industrialism, liberalism, and democracy were generally reached in this order. But in Germany they all appeared about the same time. To the Germans it appeared that they could achieve nationalism and industrialism (both of which they wanted) more rapidly and more successfully if they sacrificed liberalism and democracy. Thus, in Germany nationalism was achieved in an undemocratic way, by “blood and iron,” as Bismarck put it, while industrialism was achieved under state auspices rather than through liberalism. This selection of elements and the resulting playing off of elements against one another was possible in more peripheral areas only because these areas had the earlier experience of western Europe to study, copy, avoid, or modify. Sometimes they had to modify these traits as they developed. This can be seen from the following considerations. When the Industrial Revolution began in England and France, these countries were able to raise the necessary capital for new factories because they already had the Agricultural Revolution and because, as the earliest producers of industrial goods, they made excessive profits which could be used to provide capital. But in Germany and in Russia, capital was much more difficult to find, because they obtained the Industrial Revolution later, when they had to compete with England and France, and could not earn such large profits and also because they did not already have an established Agricultural Revolution on which to build their Industrial Revolution. Accordingly, while Western Europe, with plenty of capital and cheap, democratic weapons, could finance its industrialization with liberalism and democracy, central and eastern Europe had difficulty financing industrialism, and there the process was delayed to a period when cheap and simple democratic weapons were being replaced by expensive and complicated weapons. This meant that the capital for railroads and factories had to be raised with government assistance; liberalism waned; rising nationalism encouraged this tendency; and the undemocratic nature of existing weapons made it clear that both liberalism and democracy were living a most precarious existence. As a consequence of situations such as this, some of the traits which arose in Western Europe in the nineteenth century moved outward to more peripheral areas of Europe and Asia with great difficulty and for only a brief period. Among these less sturdy traits of Western Europe’s great century we might mention liberalism, democracy, the parliamentary system, optimism, and the belief in inevitable progress. These were, we might say, flowers of such delicate nature that they could not survive any extended period of stormy weather. That the twentieth century subjected them to long periods of very stormy weather is clear when we consider that it brought a world economic depression sandwiched between two world wars.

TRAGEDY AND HOPE A History of THE WORLD in Our Time

Carroll Quigley

Western Civilization’s conquest of the techniques of production are so outstanding that they have been honored by the term “revolution” in all history books concerned with the subject. The conquest of the problem of producing food, known as the Agricultural Revolution, began in England as long ago as the early eighteenth century, say about 1725. The conquest of the problem of producing manufactured goods, known as the Industrial Revolution, also began in England, about fifty years after the Agricultural Revolution, say about 1775. The relationship of these two “revolutions” to each other and to the “revolution” in sanitation and public health and the differing rates at which these three “revolutions” diffused is of the greatest importance for understanding both the history of Western Civilization and its impact on other societies. Agricultural activities, which provide the chief food supply of all civilizations, drain the nutritive elements from the soil. Unless these elements are replaced, the productivity of the soil will be reduced to a dangerously low level. In the medieval and early modern period of European history, these nutritive elements, especially nitrogen, were replaced through the action of the weather by leaving the land fallow either one year in three or even every second year. This had the effect of reducing the arable land by half or one-third. The Agricultural Revolution was an immense step forward, since it replaced the year of fallowing with a leguminous crop whose roots increased the supply of nitrogen in the soil by capturing this gas from the air and fixing it in the soil in a form usable by plant life. Since the leguminous crop which replaced the fallow year of the older agricultural cycle was generally a crop like alfalfa, clover, or sainfoin which provided feed for cattle, this Agricultural Revolution not only increased the nitrogen content of the soil for subsequent crops of grain but also increased the number and quality of farm animals, thus increasing the supply of meat and animal products for food, and also increasing the fertility of the soil by increasing the supply of animal manure for fertilizers. The net result of the whole Agricultural Revolution was an increase in both the quantity and the quality of food. Fewer men were able to produce so much more food that many men were released from the burden of producing it and could devote their attention to other activities, such as government, education, science, or business. It has been said that in 1700 the agricultural labor of twenty persons was required in order to produce enough food for twenty-one persons, while in some areas, by 1900, three persons could produce enough food for twenty-one persons, thus releasing seventeen persons for nonagricultural activities. This Agricultural Revolution which began in England before 1725 reached France after 1800, but did not reach Germany or northern Italy until after 1830. As late as 1900 it had hardly spread at all into Spain, southern Italy and Sicily, the Balkans, or eastern Europe generally. In Germany, about 1840, this Agricultural Revolution was given a new boost forward by the introduction of the use of chemical fertilizers, and received another boost in the United States after 1880 by the introduction of farm machinery which reduced the need for human labor. These same two areas, with contributions from some other countries, gave another considerable boost to agricultural output after 1900 by the introduction of new seeds and better crops through seed selection and hybridization. These great agricultural advances after 1725 made possible the advances in industrial production after 1775 by providing the food and thus the labor for the growth of the factory system and the rise of industrial cities. Improvements in sanitation and medical services after 1775 contributed to the same end by reducing the death rate and by making it possible for large numbers of persons to live in cities without the danger of epidemics.

TRAGEDY AND HOPE A History of THE WORLD in Our Time

Carroll Quigley

In effect, this creation of paper claims greater than the reserves available means that bankers were creating money out of nothing. The same thing could be done in another way, not by note-issuing banks but by deposit banks. Deposit bankers discovered that orders and checks drawn against deposits by depositors and given to third persons were often not cashed by the latter but were deposited to their own accounts. Thus there were no actual movements of funds, and payments were made simply by bookkeeping transactions on the accounts. Accordingly, it was necessary for the banker to keep on hand in actual money (gold, certificates, and notes) no more than the fraction of deposits likely to be drawn upon and cashed; the rest could be used for loans, and if these loans were made by creating a deposit for the borrower, who in turn would draw checks upon it rather than withdraw it in money, such “created deposits” or loans could also be covered adequately by retaining reserves to only a fraction of their value. Such created deposits also were a creation of money out of nothing, although bankers usually refused to express their actions, either note issuing or deposit lending, in these terms. William Paterson, however, on obtaining the charter of the Bank of England in 1694, to use the moneys he had won in privateering, said, “The Bank hath benefit of interest on all moneys which it creates out of nothing.” This was repeated by Sir Edward Holden, founder of the Midland Bank, on December 18, 1907, and is, of course, generally admitted today. This organizational structure for creating means of payment out of nothing, which we call credit, was not invented by England but was developed by her to become one of her chief weapons in the victory over Napoleon in 1815. The emperor, as the last great mercantilist, could not see money in any but concrete terms, and was convinced that his efforts to fight wars on the basis of “sound money,’’ by avoiding the creation of credit, would ultimately win him a victory by bankrupting England. He was wrong, although the lesson has had to be relearned by modern financiers in the twentieth century. Britain’s victory over Napoleon was also helped by two economic innovations: the Agricultural Revolution, which was well established there in 1720, and the Industrial Revolution, which was equally well established there by 1776, when Watt patented his steam engine. The Industrial Revolution, like the Credit Revolution, has been much misunderstood, both at the time and since. This is unfortunate, as each of these has great significance, both to advanced and to underdeveloped countries, in the twentieth century. The Industrial Revolution was accompanied by a number of incidental features, such as growth of cities through the factory system, the rapid growth of an unskilled labor supply (the proletariat), the reduction of labor to the status of a commodity in the competitive market, and the shifting of ownership of tools and equipment from laborers to a new social class of entrepreneurs. None of these constituted the essential feature of industrialism, which was, in fact, the application of nonliving power to the productive process. This application, symbolized in the steam engine and the water wheel, in the long run served to reduce or eliminate the relative significance of unskilled labor and the use of human or animal energy in the productive process (automation) and to disperse the productive process from cities, but did so, throughout, by intensifying the vital feature of the system, the use of energy from sources other than living bodies. In this continuing process, Britain’s early achievement of industrialism gave it such great profits that these, combined with the profits derived earlier from commercial capitalism and the simultaneous profits derived from the unearned rise in land values from new cities and mines, made its early industrial enterprises largely self-financed or at least locally financed. They were organized in proprietorships and partnerships, had contact with local deposit banks for short-term current loans, but had little to do with international bankers, investment banks, central governments, or corporative forms of business organization. This early stage of industrial capitalism, which lasted in England from about 1770 to about 1850, was shared to some extent with Belgium and even France, but took quite different forms in the United States, Germany, and Italy, and almost totally different forms in Russia or Asia. The chief reason for these differences was the need for raising funds (capital) to pay for the rearrangement of the factors of production (land, labor, materials, skill, equipment, and so on) which industrialism required. Northwestern Europe, and above all England, had large savings for such new enterprises. Central Europe and North America had much less, while eastern and southern Europe had very little in private hands. The more difficulty an area had in mobilizing capital for industrialization, the more significant was the role of investment bankers and of governments in the industrial process. In fact, the early forms of industrialism based on textiles, iron, coal, and steam spread so slowly from England to Europe that England was itself entering upon the next stage, financial capitalism, by the time Germany and the United States (about 1850) were just beginning to industrialize. This new stage of financial capitalism, which continued to dominate England, France, and the United States as late as 1930, was made necessary by the great mobilizations of capital needed for railroad building after 1830. The capital needed for railroads, with their enormous expenditures on track and equipment, could not be raised from single proprietorships or partnerships or locally, but, instead, required a new form of enterprise—the limited-liability stock corporation—and a new source of funds—the international investment banker who had, until then, concentrated his attention almost entirely on international flotations of government bonds. The demands of railroads for equipment carried this same development, almost at once, into steel manufacturing and coal mining.

Quigley, Carroll. Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (pp. 65-67). GSG & Associates Publishers. Kindle Edition.

FINANCIAL CAPITALISM, 1850-I93I This third stage of capitalism is of such overwhelming significance in the history of the twentieth century, and its ramifications and influences have been so subterranean and even occult, that we may be excused if we devote considerate attention to its organization and methods. Essentially what it did was to take the old disorganized and localized methods of handling money and credit and organize them into an integrated system, on an international basis, which worked with incredible and well-oiled facility for many decades. The center of that system was in London, with major offshoots in New York and Paris, and it has left, as its greatest achievement, an integrated banking system and a heavily capitalized—if now largely obsolescent—framework of heavy industry, reflected in railroads, steel mills, coal mines, and electrical utilities. This system had its center in London for four chief reasons. First was the great volume of savings in England, resting on England’s early successes in commercial and industrial capitalism. Second was England’s oligarchic social structure (especially as reflected in its concentrated landownership and limited access to educational opportunities) which provided a very inequitable distribution of incomes with large surpluses coming to the control of a small, energetic upper class. Third was the fact that this upper class was aristocratic but not noble, and thus, based on traditions rather than birth, was quite willing to recruit both money and ability from lower levels of society and even from outside the country, welcoming American heiresses and central-European Jews to its ranks, almost as willingly as it welcomed monied, able, and conformist recruits from the lower classes of Englishmen, whose disabilities from educational deprivation, provincialism, and Nonconformist (that is non-Anglican) religious background generally excluded them from the privileged aristocracy. Fourth (and by no means last) in significance was the skill in financial manipulation, especially on the international scene, which the small group of merchant bankers of London had acquired in the period of commercial and industrial capitalism and which lay ready for use when the need for financial capitalist innovation became urgent. The merchant bankers of London had already at hand in 1810-1850 the Stock Exchange, the Bank of England, and the London money market when the needs of advancing industrialism called all of these into the industrial world which they had hitherto ignored. In time they brought into their financial network the provincial banking centers, organized as commercial banks and savings banks, as well as insurance companies, to form all of these into a single financial system on an international scale which manipulated the quantity and flow of money so that they were able to influence, if not control, governments on one side and industries on the other. The men who did this, looking backward toward the period of dynastic monarchy in which they had their own roots, aspired to establish dynasties of international bankers and were at least as successful at this as were many of the dynastic political rulers. The greatest of these dynasties, of course, were the descendants of Meyer Amschel Rothschild (1743-1812) of Frankfort, whose male descendants, for at least two generations, generally married first cousins or even nieces. Rothschild’s five sons, established at branches in Vienna, London, Naples, and Paris, as well as Frankfort, cooperated together in ways which other international banking dynasties copied but rarely excelled. In concentrating, as we must, on the financial or economic activities of international bankers, we must not totally ignore their other attributes. They were, especially in later generations, cosmopolitan rather than nationalistic; they were a constant, if weakening, influence for peace, a pattern established in 1830 and 1840 when the Rothschilds threw their whole tremendous influence successfully against European wars. They were usually highly civilized, cultured gentlemen, patrons of education and of the arts, so that today colleges, professorships, opera companies, symphonies, libraries, and museum collections still reflect their munificence. For these purposes they set a pattern of endowed foundations which still surround us today. The names of some of these banking families are familiar to all of us and should be more so. They include Baring, Lazard, Erlanger, Warburg, Schroder, Seligman, the Speyers, Mirabaud, Mallet, Fould, and above all Rothschild and Morgan. Even after these banking families became fully involved in domestic industry by the emergence of financial capitalism, they remained different from ordinary bankers in distinctive ways: (i) they were cosmopolitan and international; (2) they were close to governments and were particularly concerned with questions of government debts, including foreign government debts, even in areas which seemed, at first glance, poor risks, like Egypt, Persia, Ottoman Turkey, Imperial China, and Latin America; (3) their interests were almost exclusively in bonds and very rarely in goods, since they admired “liquidity” and regarded commitments in commodities or even real estate as the first step toward bankruptcy; (4) they were, accordingly, fanatical devotees of deflation (which they called “sound” money from its close associations with high interest rates and a high value of money) and of the gold standard, which, in their eyes, symbolized and ensured these values; and (5) they were almost equally devoted to secrecy and the secret use of financial influence in political life. These bankers came to be called “international bankers” and, more particularly, were known as “merchant bankers” in England, “private bankers” in France, and “investment bankers” in the United States. In all countries they carried on various kinds of banking and exchange activities, but everywhere they were sharply distinguishable from other, more obvious, kinds of banks, such as savings banks or commercial banks.

Quigley, Carroll. Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (pp. 67-69). GSG & Associates Publishers. Kindle Edition.

As a result of this situation, the elected official from 1840 to 1880 found himself under pressure from three directions: from the popular electorate which provided him with the votes necessary for election, from the party machine which provided him with the nomination to run for office as well as the patronage appointments by which he could reward his followers, and from the wealthy economic interests which gave him the money for campaign expenses with, perhaps, a certain surplus for his own pocket. This was a fairly workable system, since the three forces were approximately equal, the advantage, if any, resting with the party machine. This advantage became so great in the period 1865-1880 that the forces of finance, commerce, and industry were forced to contribute ever-increasing largesse to the political machines in order to obtain the services from government which they regarded as their due, services such as higher tariffs, land grants to railroads, better postal services, and mining or timber concessions. The fact that these forces of finance and business were themselves growing in wealth and power made them increasingly restive under the need to make constantly larger contributions to party political machines. Moreover, these economic tycoons increasingly felt it to be unseemly that they should be unable to issue orders but instead have to negotiate as equals in order to obtain services or favors from party bosses. By the late 1870’s business leaders determined to make an end to this situation by cutting with one blow the taproot of the system of party machines, namely, the patronage system. This system, which they called by the derogatory term “spoils system,” was objectionable to big business not so much because it led to dishonesty or inefficiency but because it made the party machines independent of business control by giving them a source of income (campaign contributions from government employees) which was independent of business control. If this source could be cut off or even sensibly reduced, politicians would be much more dependent upon business contributions for campaign expenses. At a time when the growth of a mass press and of the use of chartered trains for political candidates were greatly increasing the expense of campaigning for office, any reduction in campaign contributions from officeholders would inevitably make politicians more subservient to business. It was with this aim in view that civil service reform began in the Federal government with the Pendleton Bill of 1883. As a result, the government was controlled with varying degrees of completeness by the forces of investment banking and heavy industry from 1884 to 1933. This period, 1884-1933, was the period of financial capitalism in which investment bankers moving into commercial banking and insurance on one side and into railroading and heavy industry on the other were able to mobilize enormous wealth and wield enormous economic, political, and social power. Popularly known as “Society,” or the “400,” they lived a life of dazzling splendor. Sailing the ocean in great private yachts or traveling on land by private trains, they moved in a ceremonious round between their spectacular estates and town houses in Palm Beach, Long Island, the Berkshires, Newport, and Bar Harbor; assembling from their fortress-like New York residences to attend the Metropolitan Opera under the critical eye of Mrs. Astor; or gathering for business meetings of the highest strategic level in the awesome presence of J. P. Morgan himself. The structure of financial controls created by the tycoons of “Big Banking” and “Big Business” in the period 1880-1933 was of extraordinary complexity, one business fief being built on another, both being allied with semi-independent associates, the whole rearing upward into two pinnacles of economic and financial power, of which one, centered in New York, was headed by J. P. Morgan and Company, and the other, in Ohio, was headed by the Rockefeller family. When these two cooperated, as they generally did, they could influence the economic life of the country to a large degree and could almost control its political life, at least on the Federal level. The former point can be illustrated by a few facts. In the United States the number of billion-dollar corporations rose from one in 1909 (United States Steel, controlled by Morgan) to fifteen in 1930. The share of all corporation assets held by the 200 largest corporations rose from 32 percent in 1909 to 49 percent in 1930 and reached 57 percent in 1939. By 1930 these 200 largest corporations held 49.2 percent of the assets of all 40,000 corporations in the country ($81 billion out of $165 billion); they held 38 percent of all business wealth, incorporated or unincorporated (or $81 billion out of $212 billion); and they held 22 percent of all the wealth in the country (or $81 billion out of $367 billion). In fact, in 1930, one corporation (American Telephone and Telegraph, controlled by Morgan) had greater assets than the total wealth in twenty-one states of the Union. The influence of these business leaders was so great that the Morgan and Rockefeller groups acting together, or even Morgan acting alone, could have wrecked the economic system of the country merely by throwing securities on the stock market for sale, and, having precipitated a stock-market panic, could then have bought back the securities they had sold but at a lower price. Naturally, they were not so foolish as to do this, although Morgan came very close to it in precipitating the “panic of 1907,” but they did not hesitate to wreck individual corporations, at the expense of the holders of common stocks, by driving them to bankruptcy. In this way, to take only two examples, Morgan wrecked the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad before 1914 by selling to it, at high prices, the largely valueless securities of myriad New England steamship and trolley lines; and William Rockefeller and his friends wrecked the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railroad before 1925 by selling to it, at excessive prices, plans to electrify to the Pacific, copper, electricity, and a worthless branch railroad (the Gary Line). These are but examples of the discovery by financial capitalists that they made money out of issuing and selling securities rather than out of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and accordingly led them to the point where they discovered that the exploiting of an operating company by excessive issuance of securities or the issuance of bonds rather than equity securities not only was profitable to them but made it possible for them to increase their profits by bankruptcy of the firm, providing fees and commissions of reorganization as well as the opportunity to issue new securities.

Quigley, Carroll. Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (pp. 88-90). GSG & Associates Publishers. Kindle Edition.

This period, 1884-1933, was the period of financial capitalism in which investment bankers moving into commercial banking and insurance on one side and into railroading and heavy industry on the other were able to mobilize enormous wealth and wield enormous economic, political, and social power. Popularly known as “Society,” or the “400,” they lived a life of dazzling splendor. Sailing the ocean in great private yachts or traveling on land by private trains, they moved in a ceremonious round between their spectacular estates and town houses in Palm Beach, Long Island, the Berkshires, Newport, and Bar Harbor; assembling from their fortress-like New York residences to attend the Metropolitan Opera under the critical eye of Mrs. Astor; or gathering for business meetings of the highest strategic level in the awesome presence of J. P. Morgan himself. The structure of financial controls created by the tycoons of “Big Banking” and “Big Business” in the period 1880-1933 was of extraordinary complexity, one business fief being built on another, both being allied with semi-independent associates, the whole rearing upward into two pinnacles of economic and financial power, of which one, centered in New York, was headed by J. P. Morgan and Company, and the other, in Ohio, was headed by the Rockefeller family. When these two cooperated, as they generally did, they could influence the economic life of the country to a large degree and could almost control its political life, at least on the Federal level. The former point can be illustrated by a few facts. In the United States the number of billion-dollar corporations rose from one in 1909 (United States Steel, controlled by Morgan) to fifteen in 1930. The share of all corporation assets held by the 200 largest corporations rose from 32 percent in 1909 to 49 percent in 1930 and reached 57 percent in 1939. By 1930 these 200 largest corporations held 49.2 percent of the assets of all 40,000 corporations in the country ($81 billion out of $165 billion); they held 38 percent of all business wealth, incorporated or unincorporated (or $81 billion out of $212 billion); and they held 22 percent of all the wealth in the country (or $81 billion out of $367 billion). In fact, in 1930, one corporation (American Telephone and Telegraph, controlled by Morgan) had greater assets than the total wealth in twenty-one states of the Union.

Quigley, Carroll. Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (p. 89). GSG & Associates Publishers. Kindle Edition.

The occupation of the United States had given rise to three chief geographic sections: a commercial and later financial and industrial East, an agrarian and later industrial West, and an agrarian South. Unfortunately, the two agrarian sections were organized quite differently, the South on the basis of slave labor and the West on the basis of free labor. On this question the East allied with the West to defeat the South in the Civil War (1861-1865) and to subject it to a prolonged military occupation as a conquered territory (1865-1877). Since the war and the occupation were controlled by the new Republican Party, the political organization of the country became split on a sectional basis: the South refused to vote Republican until 1928, and the West refused to vote Democratic until 1932. In the East the older families which inclined toward the Republican Party because of the Civil War were largely submerged by waves of new immigrants from Europe, beginning with Irish and Germans after 1846 and continuing with even greater numbers from eastern Europe and Mediterranean Europe after 1890. These new immigrants of the eastern cities voted Democratic because of religious, economic, and cultural opposition to the upper-class Republicans of the same eastern section. The class basis in voting patterns in the East and the sectional basis in voting in the South and West proved to be of major political significance after 1880.

Quigley, Carroll. Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (p. 87). GSG & Associates Publishers. Kindle Edition.

The influence of these business leaders was so great that the Morgan and Rockefeller groups acting together, or even Morgan acting alone, could have wrecked the economic system of the country merely by throwing securities on the stock market for sale, and, having precipitated a stock-market panic, could then have bought back the securities they had sold but at a lower price. Naturally, they were not so foolish as to do this, although Morgan came very close to it in precipitating the “panic of 1907,” but they did not hesitate to wreck individual corporations, at the expense of the holders of common stocks, by driving them to bankruptcy. In this way, to take only two examples, Morgan wrecked the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad before 1914 by selling to it, at high prices, the largely valueless securities of myriad New England steamship and trolley lines; and William Rockefeller and his friends wrecked the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railroad before 1925 by selling to it, at excessive prices, plans to electrify to the Pacific, copper, electricity, and a worthless branch railroad (the Gary Line). These are but examples of the discovery by financial capitalists that they made money out of issuing and selling securities rather than out of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and accordingly led them to the point where they discovered that the exploiting of an operating company by excessive issuance of securities or the issuance of bonds rather than equity securities not only was profitable to them but made it possible for them to increase their profits by bankruptcy of the firm, providing fees and commissions of reorganization as well as the opportunity to issue new securities.

Quigley, Carroll. Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (pp. 89-90). GSG & Associates Publishers. Kindle Edition.

MAKING THE COMMONWEALTH, 1910-1926 As soon as South Africa was united in 1910, the Kindergarten returned to London to try to federate the whole empire by the same methods. They were in a hurry to achieve this before the war with Germany which they believed to be approaching. With Abe Bailey money they founded The Round Table under Kerr’s (Lothian’s) editorship, met in formal conclaves presided over by Milner to decide the fate of the empire, and recruited new members to their group, chiefly from New College, of which Milner was a fellow. The new recruits included a historian, F. S. Oliver, (Sir) Alfred Zimmern, (Sir) Reginald Coupland, Lord Lovat, and Waldorf (Lord) Astor. Curtis and others were sent around the world to organize Round Table groups in the chief British dependencies. For several years (1910-1916) the Round Table groups worked desperately trying to find an acceptable formula for federating the empire. Three books and many articles emerged from these discussions, but gradually it became clear that federation was not acceptable to the English-speaking dependencies. Gradually, it was decided to dissolve all formal bonds between these dependencies, except, perhaps, allegiance to the Crown, and depend on the common outlook of Englishmen to keep the empire together. This involved changing the name “British Empire” to “Commonwealth of Nations,” as in the title of Curtis’s book of 1916, giving the chief dependencies, including India and Ireland, their complete independence (but gradually and by free gift rather than under duress), working to bring the United States more closely into this same orientation, and seeking to solidify the intangible links of sentiment by propaganda among financial, educational, and political leaders in each country.

Quigley, Carroll. Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (pp. 159-160). GSG & Associates Publishers. Kindle Edition.

In the last 20 years, the United States has been freefalling like Tom Petty, and Russia is run by the most popular politician in the world, Vladimir Putin. Sure he ran the KGB, and perhaps he has disposed of a few (dozen) bodies over the years (allegedly), but we’ve all done crazy things in our youth that we might not be proud of. In all seriousness, Vladimir Putin has the respect of the vast majority of the voters in Russia because people actually believe him, and they have listened to him explain the realities of global politics in a way that makes more sense to people.

Robinson, Charlie. The Octopus of Global Control (p. 226). Kindle Edition.

“No one outside America any longer believes the US media or the US government. You can't believe a word the American media says. If they say anything correctly, it's just an accident.” - Paul Craig Roberts, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Economic Policy under President Reagan.

Robinson, Charlie. The Octopus of Global Control (p. 327). Kindle Edition.

The BIS is undeniably the world’s most secretive global financial institution whose sole mission is to further the interests of central banks. In doing so, it has spawned a new class of close-knit global technocratic pricks whose members rotate between cushy positions at the BIS, the IMF, the World Bank, and central and commercial banks throughout the world.

Robinson, Charlie. The Octopus of Global Control (pp. 258-259). Kindle Edition.

The measures adopted to restore public order are, first of all, the elimination of the so-called subversive elements. They were elements of disorder and subversion. On the morrow of each conflict, I gave the categorical order to confiscate the largest possible number of weapons of every sort and kind. This confiscation, which continues with the utmost energy, has given satisfactory results.” – Benito Mussolini, address to the Italian Senate, 1931. Well, he didn’t confiscate all of the guns. Some of his people shot him and his wife in the head, then strung them upside down from a light pole.

Robinson, Charlie. The Octopus of Global Control (p. 76). Kindle Edition.

If the opposition disarms, well and good. If it refuses to disarm, we shall disarm it ourselves.” – Joseph Stalin. 1929. The Soviet Union established gun control. From 1929 to 1953, about 20 million dissidents were rounded up and exterminated. By 1987 that figure had risen to 61,911,000.

Robinson, Charlie. The Octopus of Global Control (p. 76). Kindle Edition.

The last two sections bring us closer to understanding how a living system might work. They tell us that in order to absorb energy, the living system must store information about the environment. And that to store information, the system needs energy.

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-25962-4

It is a system which has conscripted vast human and material resources into the building of a tightly knit, highly efficient machine that combines military, diplomatic, intelligence, economic, scientific and political operations. Its preparations are concealed, not published. Its mistakes are buried, not headlined. Its dissenters are silenced, not praised. No expenditure is questioned, no rumor is printed, no secret is revealed.” ― John F. Kennedy, former President of the United States, April 27, 1961. The history scholars will tell you that the context of Kennedy’s speech was regarding the spreading of Communism throughout the world. Perhaps it was meant to sound like a speech about Communism, and it worked to provide him cover, should anyone ever question it, but you have to read between the lines. He couldn’t come right out and say “the Globalists that are running this planet are total lunatics and they are going to get us all killed”, as much as we think he would have loved to say that. His predecessor, President Eisenhower, used his outgoing Presidential speech a few weeks earlier to warn us about the consolidation of power within the American government and certain segments of the private sector that he saw as a very real threat to the world. Kennedy understood very clearly what Eisenhower was talking about, and it was something far worse than Communism. It was the emergence of the New World Order.

Robinson, Charlie. The Octopus of Global Control (pp. 18-19). Kindle Edition.

All political power comes from the barrel of the gun. You register and ban the firearms before the slaughter.” – Mao Tse Tung,

November 6, 1938. China established gun control in 1935. From 1948 to 1952, a total of 10,076,000 political dissidents, unable to defend themselves, were rounded up and exterminated in Kuomintang China, and by 1987, another 35,236,000 people were murdered under the Communists.

Robinson, Charlie. The Octopus of Global Control (pp. 75-76). Kindle Edition.

“It is well enough that people of the nation do not understand our banking and monetary system, for if they did, I believe there would be a revolution before tomorrow morning.” - Henry Ford, Founder, Ford Motors.

Robinson, Charlie. The Octopus of Global Control (p. 250). Kindle Edition.

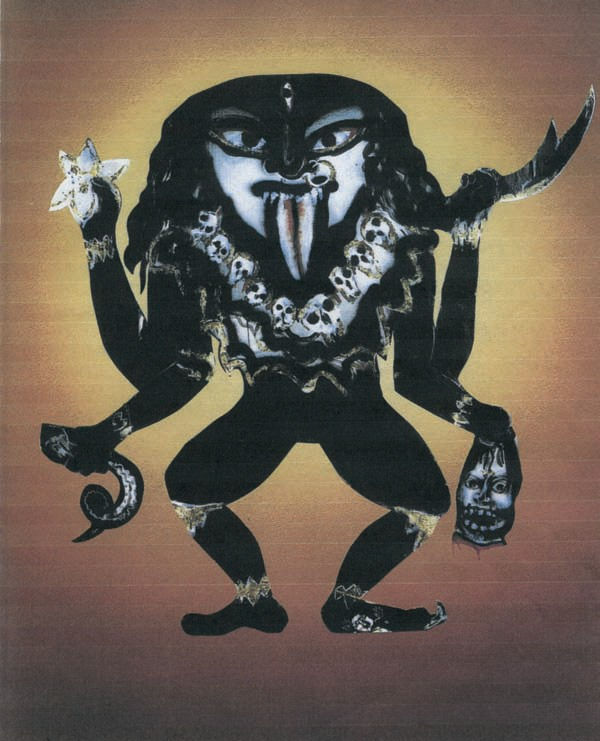

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/kali-and-her-tongue/articleshow/10816142.cms?from=mdr

The Black Sun: The Alchemy and Art of Darkness: Carolyn and Ernest Fay Series in Analytical Psychology

Plate 4. Picture of Kali as painted by Maitreya Bowen.

From Ajit Mookerjee, Kali: The Feminine Force, p. 93.

AI Overview

Learn more…Opens in new tab

Microsatellite markers, also known as simple sequence repeats (SSRs), are a common genetic marker used in population genetics to estimate genetic diversity. SSRs are DNA segments that contain repetitive motifs of 1–6 nucleotides, which are repeated 5–50 times. They are often found in intergenic regions, but can also be found in intron, exon, and untranslated regions. SSRs have a higher mutation rate than other DNA areas, which leads to high genetic diversity.

SSRs are useful for many reasons, including:

-

Wild species: SSRs can be used to study diversity based on genetic distance, estimate gene flow and crossing over rates, and infer infraspecific genetic relations.

-

Plant genotyping: SSRs are the most commonly used markers for plant genotyping because they are codominant, highly informative, and can be transferred between related species. They are also relatively low cost and can be used by small labs.

-

Cultivar discrimination: SSR markers have been used to distinguish cultivars of ginseng.

Some other features of SSRs include:

-

Polymorphism: SSRs have high polymorphism with multiple alleles per locus.

-

Reproducibility: SSRs are experimentally reproducible.

-

Distribution: The distribution of SSRs in different gene subcategories varies by species.

AI Overview

Learn more…Opens in new tab

Microsatellite markers, also known as simple sequence repeats (SSRs), are DNA sequences that repeat 2–6 base pairs and are used in genetics to study genetic distance. SSRs are codominant, highly informative, and can be transferred between related species. They are also relatively low cost and can be used by small labs.

SSRs are useful for studying genetic distance in wild species, estimating gene flow and crossing over rates, and inferring infraspecific genetic relations. For example, one study found that increasing the number of loci used for genotyping from six to seventeen substantially decreased standard deviation estimates of interpopulation genetic distances.

SSRs are also used in other studies, such as: Kinship, Population, Gene duplication or deletion, Plant fingerprinting, and Association analysis between target traits and quantitative trait loci (QTLs).

Similarity and symmetry are related concepts in geometry and math:

Symmetry

When similar or matching parts of an object or figure mirror each other, creating a balanced and proportionate relationship. For example, a symmetrical shape can be divided into identical parts by a line that creates mirror images on either side. Symmetrical objects can be found in nature, art, and architecture. There are four main types of symmetry: translation, rotation, reflection, and glide reflection.

Similarity

When elements are stretched or shrunk in size by a scale factor, but retain their shape. For example, two triangles can be similar if their corresponding sides are proportional. Similarity symmetry can create order and unity in architectural designs, and is also related to fractals.